Shadow is not just a dark stain falling behind an object facing a solid light. It usually whispers the object’s story, making us contemplate its different existence possibilities. Its subtle margins invite viewers to pass through the gates of reality into the unknown realms.

Interdisciplinary artist Bilal Yılmaz, a dedicated explorer of his art, has unveiled his latest solo show, Elhamra: Learning From Crafts. Curated by Lydia Chatziiakovou, the show invites the audience to embark on a journey to the past of a çini ceramics production facility, Elhamra, nestled in Kütahya, a mid-west city of Turkey renowned for its unique çini ceramic production.

The artist has been researching, lecturing, and mapping the crafts in Turkey as part of Craft Net, “a tool for mapping the craft ecosystem of different cities with the participation of local creatives and institutions, that can lead to the emergence of creative communities and networks built around the contemporary potential of craft,” established with curator and researcher Lydia Chatziiakovou. His latest research about Elhamra resulted in developing a brass model of this historical tile production facility, exhibited at Pera Museum’s Souvenier’s of the Future exhibition, which ended on April 28, 2024. I remember the first time I encountered the work, shining beautifully under the warm spotlight, revealing its details that can hardly be seen while facing it in the front with the help of its shadow on the plain pearl-like surface on which it was placed. It was fascinating to witness that the moment of a shadow cannot simply be a shadow but a symbol of a significant part of the history of the crafts.

Crafts have been appreciated in the cultural history of the country. As religion forbade artisans and painters to depict any human, they navigated their way toward illustrating nature and ordinary objects as well as creating geometrical combinations in their designs for centuries, which could also be traced on tiles as well as other artifacts, such as embroiders, glass and book decoration.

The Pera Museum commissioned the artist and Lydia Chatziiakovou to conduct field research about Kütahya çini ceramics production and the ecosystem that emerged around this craft. The research period led him to the Elhamra tile production facility, which dates back to the mid-20th century.

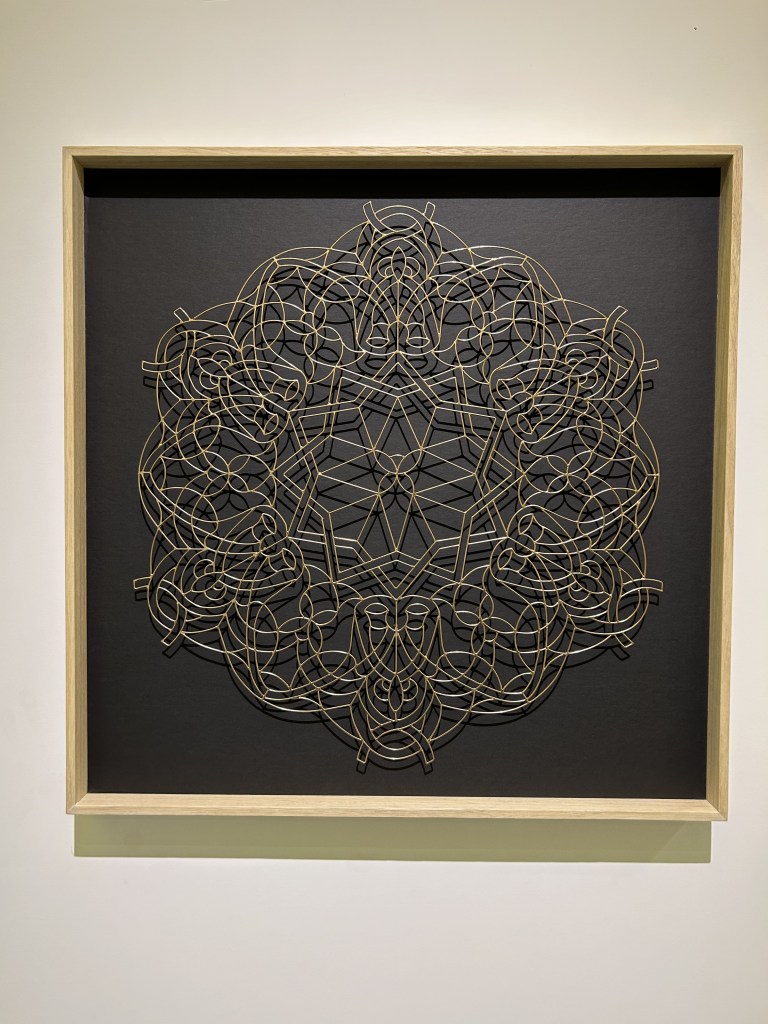

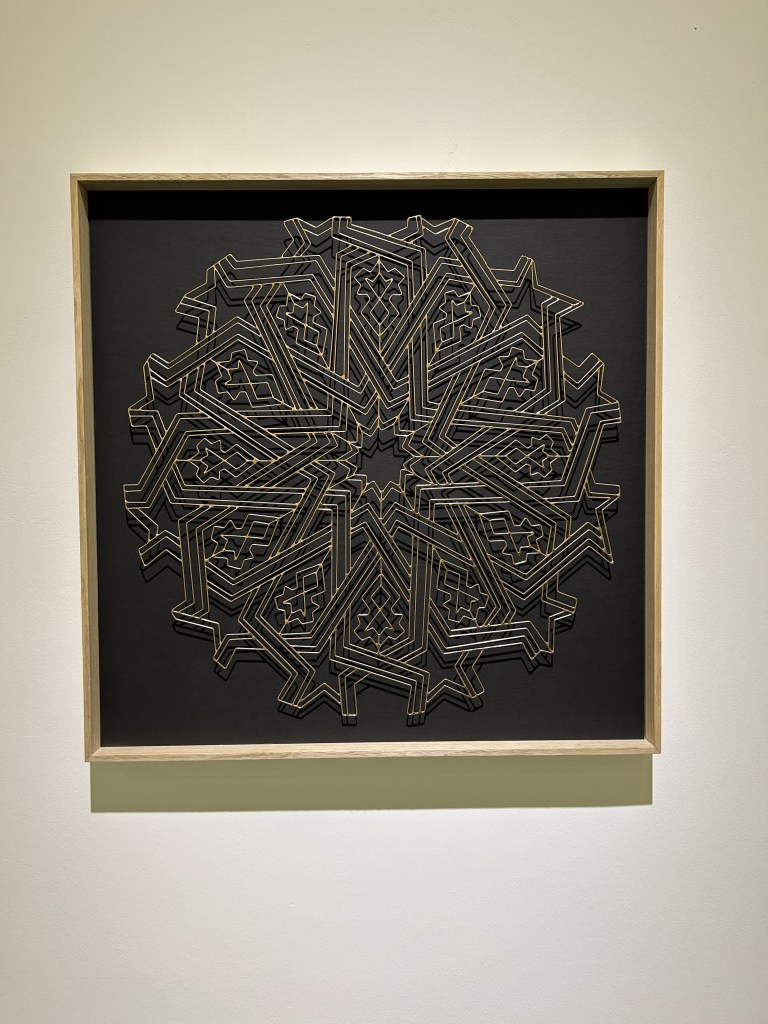

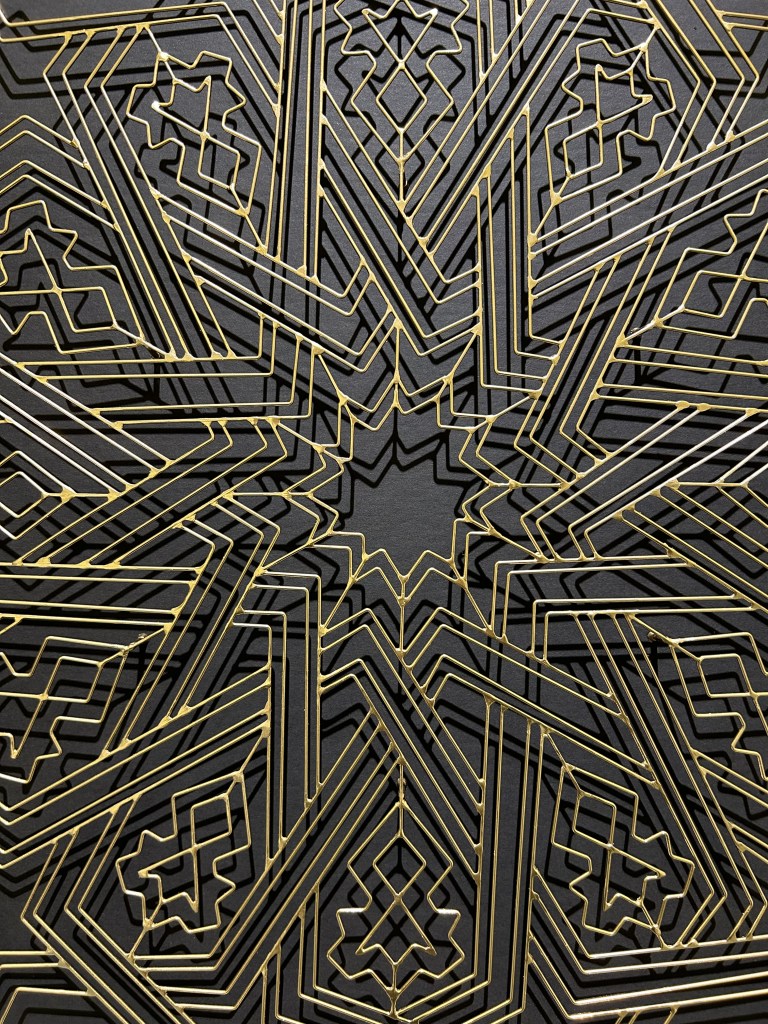

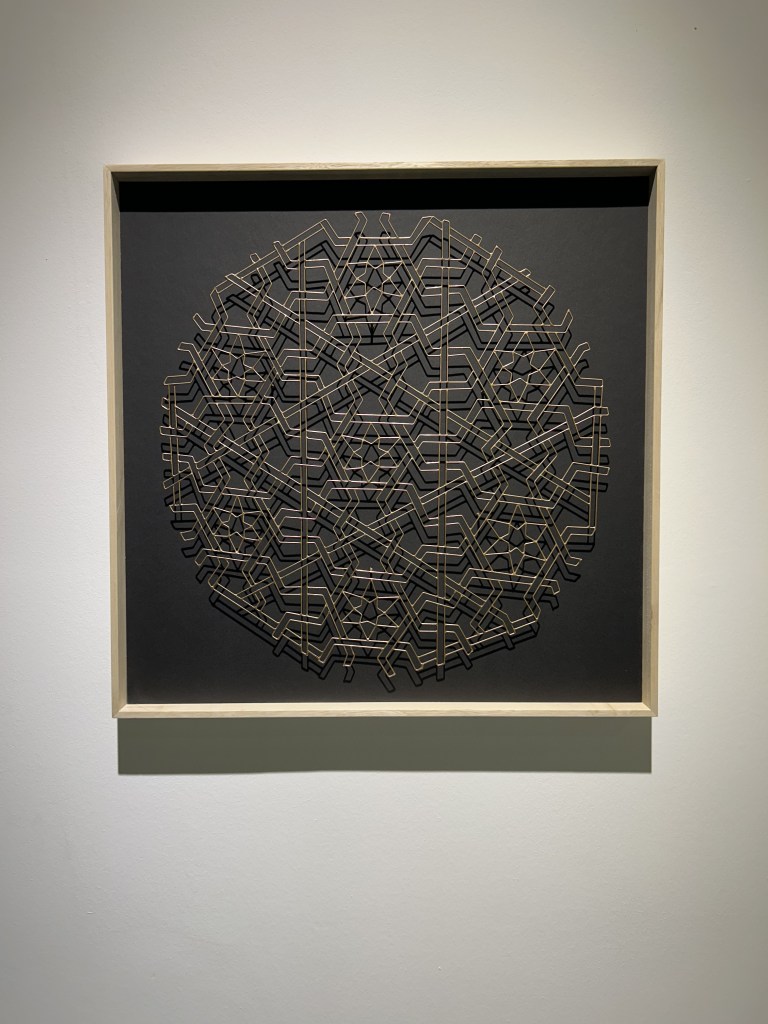

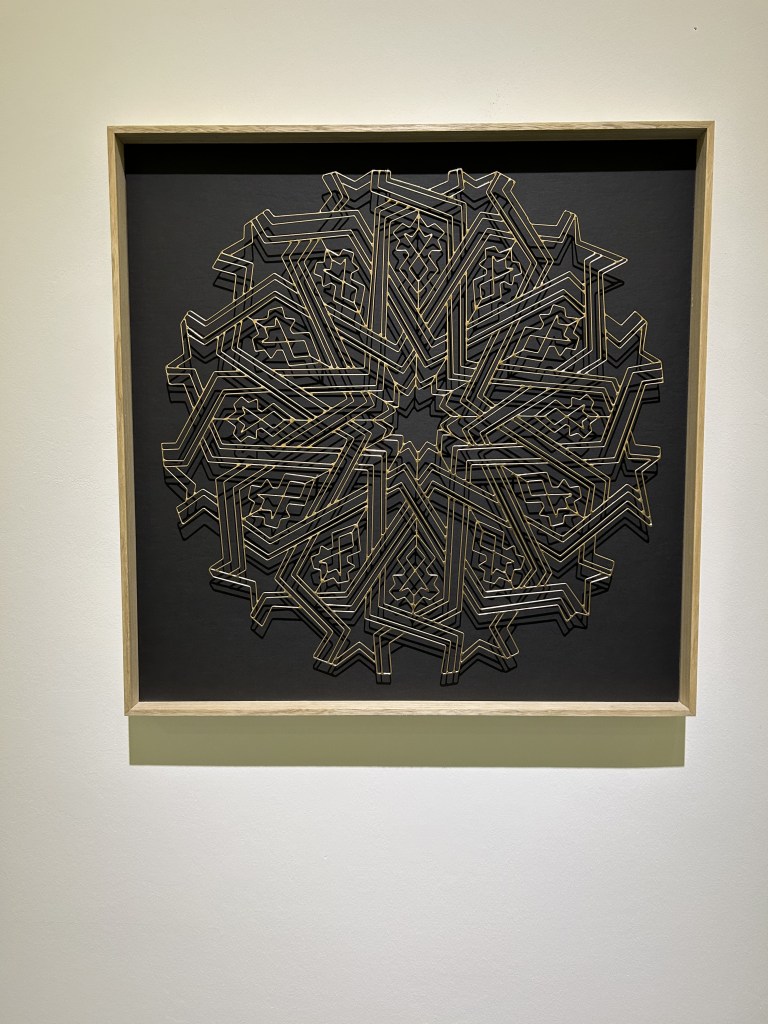

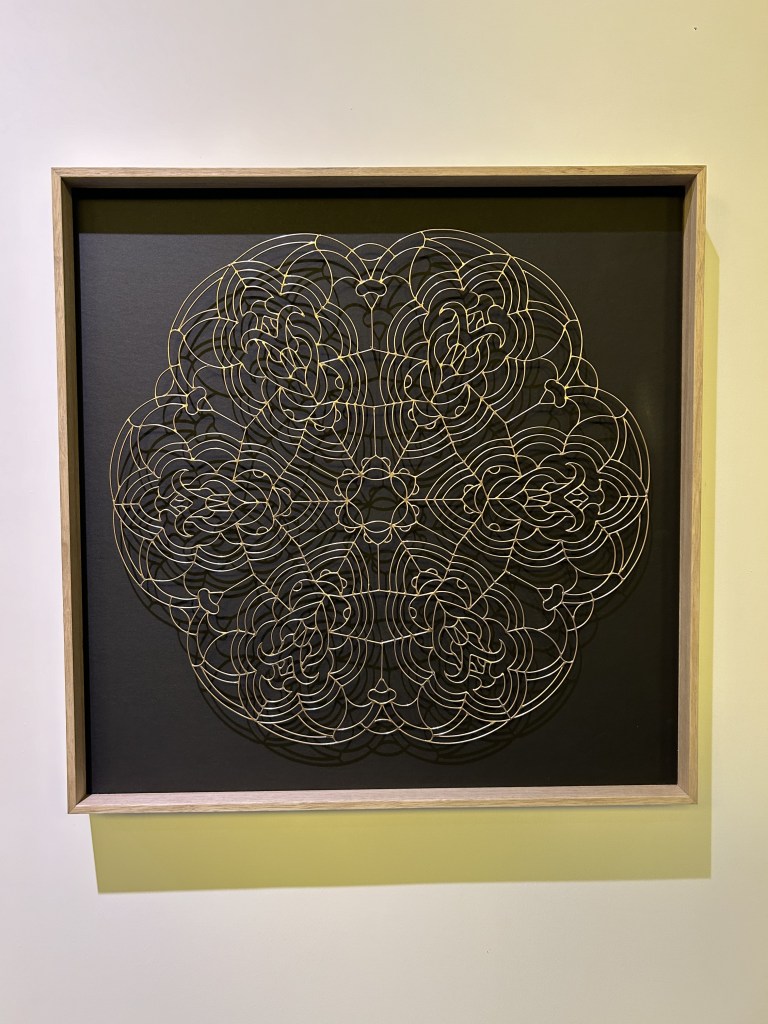

The artist approaches the heritage of tile production from a contemporary perspective. His careful study and years-long collaboration with different artisans appear in the production of the artworks displayed in the exhibition. The exhibition space welcomes the audience with a significant wall piece with a black and white foil background produced by the photographs of Elhamra. The spacious environment of the gallery allowed it to reflect the actual size of the production facility within the white cube. We see a staircase with shelves where the pots and other production materials are placed on the left side. The brass depiction of flowers and leaves with a star motif, derived from the traditional Magen David, placed in the center of the design attracts attention. A wooden stand, a brush, a tiny grinder, and other equipment found in the remaining Elhamra were placed on the left below the artwork.

The contrast between the duo-chrome foil, the greenish-gold color of brass, and the found objects created a passage in time. Even though the artwork’s form alludes to the conventional design elements, its placement, the use of comparatively complex forms, and expertise in the production harmonize it with current liking. Of course, the gap between the surface and the brass reflects a shadow, inviting the viewer to reflect on the past.

“craft is versatile, multi-layered and multi-directional”

Lydia Chatziiakovou

Lydia Chatziiakovou interprets the shadows as a chance to invite ”the viewer (…) to observe the intricate space where these patterns were created, and imagine the labour behind the final product, the relations between masters and apprentices, the transformations of the materials, and the interplay between the centuries-old, accumulated, multicultural knowledge and innovation that these transformations have taken.” To her, “craft is versatile, multi-layered and multi-directional.” Thus, the artist’s practice is “[a] transformation [which] echoes the evolution of craft through experimentation with materials and techniques; a process incorporating both tradition and innovation; collective and individual ingenuity (…).”

On the right side of the gallery space, the black-and-white foil extended on the wall with another wall piece containing a bird depiction. Birds, specifically pigeons, symbolize Jesus Christ in Western art history. The curator placed the piece under a light haze, intersecting with the bird’s head feather. I consider this placement to pay homage to the Christian artisans who also played – and still play— a crucial role in the tile production.

On the left side, the gallery space sprawls into a large rectangular shape. Right in the middle of this section, a glaze grinder operates in silence—two marble knobs whirl on the raw glaze, which is in a sand-like form. The artist derived this version from the conventional grinder used in Elhamra and other tile manufacturing factories in that period. The raw glaze is still produced in Kütahya and is used in production. While I was watching the movement of the grinder in total isolation from the crowd surrounding me, the production assistant of Bilal Yılmaz, Emrullah Büker, approached me. He started sharing information about the glaze and the dye used on the tiles and how they are unearthed today.

The gallery space unfolds toward a darker area where media works occupy the space mostly. The darker atmosphere of this section echoes the studios where the artisans work. These studios were deprived of sunlight and illuminated by the candles. The artist produced kinetic sculptures from the traditional patterns used while decorating the tiles. Flower bulbs and leaves, a star, and a bird turn around, creating a three-dimensional sculpture.

Elhamra is facing the kinetic sculpture. Emrullah emerged from the dark hall once more, making me feel like I was having a mystical experience. He approached me to share the specific sections of the production facility. He rhapsodized the divisions of the factory on its small-scale replica, which has intrinsic details. He showed me where the original grinder was located, the warehouse, and the tile drying room called “Hell.” The metal sculpture’s vertical and horizontal lines contrast with the curved lines of the wall pieces at the entrance.

The back of the room includes documentation of the conventional tile production equipment and the history of the producers. This section consists of a dia show, numerous photographs he took during his visit to Elhamra, papers used to instrumentalize the transfer of the design on tile, and the pots still in use.

I left the exhibition space with thoughts on shadow, as I would not expect to dive into my own psyche after seeing an exhibition focused on crafts. The works and the documentation were almost like an analysis a psychiatrist would do. They encouraged me to look at the darker side of existence, which does not carry solely a negative meaning; it can also represent the values we buried deep inside. It brought the neglected reality of the artisans, their working conditions, and their devotion to their practice. The exhibition displayed the “dirty” labor process in dungeon-like ateliers full of dust, rust, sweat, and grease, contrasting the super clean industrial production. To me, crafts are like working on the subconscious of material. It is heavily shaped by certain rules and patterns to follow; however, untamed in nature. It requires one to commune with the material and to develop a sense on how the material reacts to the gestures of the master. Material and the artisans react each other as a person responds to outer events. The artist’s courageous designs shed light on the bright side of the process.

Elhamra: Learning from Crafts can be visited at ArtOn Istanbul gallery, located in Piyalepaşa, the city’s most recent hip spot, until November 2, 2024.