I met Rosa Lacavalla during the 2024 Foto Festiwal, a festival based in Łódź, Poland, at its Photo Match session. I also met several talented photographers during the portfolio reviews. One received the prize distributed by the 212 Photography Istanbul photography festival, and the other traveled to Mardin to extend his ongoing project. And Rosa applied to Gate 27 with a project that takes its roots from an imaginary equator line between Italy and Argentina. I became fascinated by the idea and suggested to her that she develop a project between Ayvalık and Lesbos Island, reflecting the shared past and heritage between the two places, and apply to the residency. It gives me joy to see how these talented artists have achieved so much after our encounter. This interview aims to shed light on Rosa’s practice and her relationship with nature, daily life, and architectural elements.

Rosa likes to work with music. She prepeared a playlist for her project In the Language of Wind. You can join her sound journey via the playlist below.

Rosa, I remember the day of our portfolio review. The way you articulated your project attracted my attention. Could you share your idea and motivation for starting your project to explore the surroundings of the equator line? What have you found during this investigation, and how have these findings influenced the concept?

Before becoming a tangible project, La Festa Dell’Equatore was the result of three years of intense and stubborn research. I delved into the history of my husband’s family, who had emigrated from Italy to Argentina. Starting with just one clue – a small piece of paper with the names of his great-grandparents, a province, and two birth dates that turned out to be wrong – I felt a strong desire to reconstruct this story and give it back to those who, over the years, had wondered about these origins without finding answers.

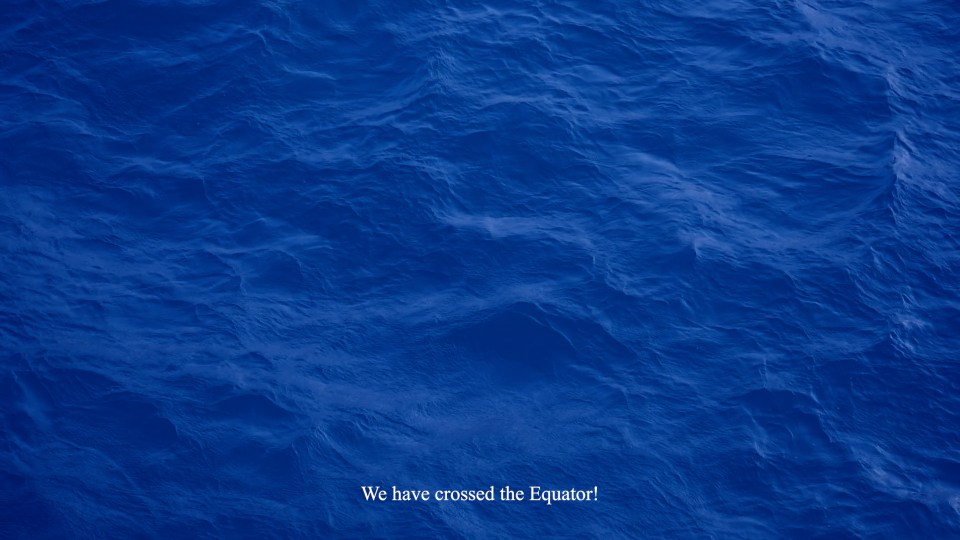

This research led me to study historical events and read the diaries of several Italian emigrants. It was through these stories that I knew about the Equator Crossing Ceremony. This ritual was performed on steamships and is still practiced today on cruise ships or private boats. It was a big celebration where a person dressed as King Neptune would issue symbolic, unofficial documents certifying the passage from one hemisphere to the other. However, what was meant to be a celebration of a new beginning often turned into a moment of profound nostalgia. Many people emigrated to escape war or hunger, or simply to seek a better life. They often had no idea where they would disembark, nor if and when they would be able to return home to their loved ones.

In addition, many would gaze at the night sky and wonder if the stars and the moon would look different once they crossed that imaginary boundary line. I then realized that my work couldn’t just be about migration. It spontaneously took on new layers, leading me toward a much more evocative visualization of these events. In this way, the migration of this family used as a case study became intertwined with the movement of the stars and, subsequently, the concept of family constellations, a therapeutic method that looks at how family patterns and transgenerational traumas affect our lives and relationships, helping us understand the links between the past and the present.

That said, the exact spot of the Equator crossing had become a meeting point of cultures, a moment for questions and reflection, and the realization that life was about to change completely.

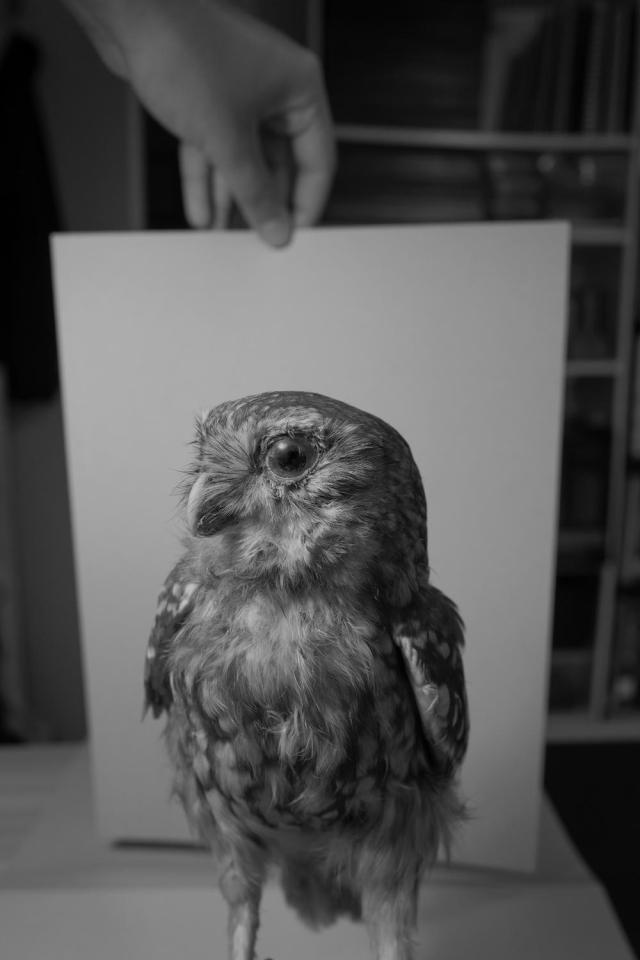

Images from the series, Voy Cerrando Los Ojos Anhelando Verte Otra Vez. Image courtesy of © Rosa Lacavalla.

You mostly photograph and exhibit the daily situations and objects that often remain unnoticed or are mundane in some way. You position these captures along with natural or architectural elements. Your series titled “Voy Cerrando Los Ojos Anhelando Verte Otra Vez” demonstrates this quality. How do you define your approach to photography in this manner?

Throughout my artistic journey, I’ve realized that I’m often drawn to small details that, while seemingly mundane to most people, I personally find fascinating.

Regarding Voy Cerrando Los Ojos Anhelando Verte Otra Vez, this was my first trip to Argentina. Buenos Aires had been described to me as an incredibly lively city at all hours of the day and night. While I can confirm that, the feeling I had was different: I sensed that the city could, at the same time, be a slow jungle, dominated by wonderful plants with unusual growth and shapes. This silent and meditative atmosphere is also reflected in the images featuring people, far from the places frequented by both international and local tourists. It’s definitely a very intimate way of narrating the world. While it started from a documentary approach, the storytelling is filtered through the emotions I feel in a specific moment or place, breathing in its atmosphere.

To truly understand the world in a broader sense, you must first get close to the small, often unnoticed details that make up its stories.

Images from the series, Sana Sana. Image courtesy of © Rosa Lacavalla.

To me, your photographs resonate a dialect between the mundane and the sublime. I get excited to see a leaf right next to a detail from the historically monumental building. It is both enjoyable to look at these photographs from a geometrical perspective, following the lines and connecting points, as well as questioning the nature and its positioning within the human-made elements. And it feels like they also try to remind us of something. Do you think that there are unseen elements in your compositions?

The unseen elements are the threads that hold the story together. My research often uses images as metaphors or as a visual representation of emotions that I wouldn’t be able to communicate otherwise, since photography is my primary medium of expression. My work Sana Sana is a particularly meaningful example of this. In that series, images take on different meanings, becoming symbolic translations of feelings. They capture moments of anxiety and comfort, unease and quiet, all while juxtaposing natural and human-made elements.

I work mainly with photographic series rather than single images. However, many of the photos I take are like fragments of a story; even when taken individually, they can evoke something in the soul of the viewer.

I am often hesitant to explain every single image, where it was taken or the exact reason for its inclusion. Of course, if asked, I’m happy to share the details, but that’s not my main goal. Explaining every single detail would risk revealing the magic and taking away the poetry I want the images to carry. Allowing these elements to remain “unseen” lets the viewer connect with the story through their own personal experiences and approach what I truly want to communicate in a completely natural way.

This approach also applies when I decide to introduce other media into my research alongside photography. Even in those cases, my aim is to create an experience that stimulates reflection and inner dialogue, leaving room for individual interpretation.

“I even started shooting in color again, something I hadn’t done in a long time.”

We talked about your educational background. You began with art graphics (printmaking) and pursued photography during your master’s studies. Could you tell us a bit about this journey? What drew you to photography?

My path was a very spontaneous one. Ever since I was a little child, I have expressed a strong desire to become a painter. Although art was a world quite distant and not fully understood by my family, they always supported me in pursuing my artistic journey.

At that time, my only real experience with photography was taking family photos, as was customary back then. However, during my adolescence, I began wanting to paint what I observed, and photography became a useful tool for capturing the subjects I wanted to turn into paintings. It didn’t take long for me to realize that photography was actually my main medium, so I started teaching myself through magazines and taking notes on what I could find on the internet when it wasn’t so easy.

When it was time for university, I moved to Bologna to enroll in the Academy of Fine Arts, despite the fact that there was no specific bachelor’s course in photography. So, I took a chance on a course whose nature I didn’t fully understand before enrolling in it. Yet, years later, I can still confirm that the path focused on printmaking (thanks also to a professor I’m still grateful to) gave me far more tools for reflecting on the world than my subsequent two-year photography studies, which included a year abroad at Coventry University in England.

Images from the series, La Festa Dell’Equatore. Image courtesy of © Rosa Lacavalla.

How was your time at Gate 27? You have visited Lesbos many times and spent a considerable amount of time in Ayvalık, exploring the town. What is the most attractive element during these visits?

In the months leading up to my arrival, I researched the most interesting and useful locations for the project I intended to develop, focusing on the cultural exchange between Turkey and Greece. I envisioned it as an “Equator,” along with everything that might revolve around it, just as I described in my previous work. This was my first visit to both countries, and after an initial period of feeling overwhelmed by all the newness, I was able to dedicate myself to deeper introspection. Being far enough from the city to listen to its distant sounds significantly influenced my vision during subsequent visits. I was particularly fascinated by the discovery of Turkish cultural elements in Mytilene and Greek architecture in Ayvalık, and elsewhere. I’ve blended these various elements, making it impossible for the viewer to distinguish which images were taken in which country. This creates a continuous exchange that runs throughout the series. The concept of “Equator” from my previous work has evolved and manifested in a new and unexpected way in Rüzgarın Dilinde (In the Language Of The Wind), becoming, most of all, the narrative of a sensory and historical exchange.

To my great surprise, the key element of this research emerged during my first few days of observation along the coast. Each day, the wind carried with it alternating sounds, in addition to its own inherent noise: the prayers from the mosques, the silence of boats followed by loud music from onboard parties, and the greetings of captains using their ship horns. I realized that this exchange was happening right before my eyes, and not just on a visual level. Because of this, I wanted to translate those sounds into images by observing the cities from a different perspective and searching for details that could narrate this historical exchange in a new light.

My time at Gate 27 was both relaxing and rejuvenating, especially from a photographic standpoint. I was coming from a period where I had stopped shooting because I was so absorbed in other aspects that an artistic career demands, such as applications, exhibition proposals, and networking. Being able to spend a month completely focused on my current research, away from the city’s frenzy, brought me back to the spontaneity of just taking photos. I was able to work on my project without feeling any pressure, and I even started shooting in color again, something I hadn’t done in a long time.

Images from the series, In the Language of the Wind Image courtesy of © Rosa Lacavalla.

You were precise about trying ceramics during your residency. We care deeply about residents trying new techniques in their artistic production. What was significant about ceramics for you?

From the very beginning, I was driven by a deep enthusiasm for an interdisciplinary approach during the residency. I was eager to experiment with new techniques and step outside my comfort zone. The inspiration for the ceramics came unexpectedly, from reading Irfan Orga’s The Caravan Moves On. Although the story wasn’t directly related to my project, the mention of Etruscan vases sparked my imagination, leading me to envision artifacts that combined elements of Anatolian and ancient Greek art. Once in Turkey, the idea of creating ceramics was immediately reinforced; not only did I notice their widespread presence in museums, but I also felt the strong tradition permeating places like Ayvalık and Çanakkale.

I understood the need to personally create these forms, conceiving them as true terracotta vessel-sculptures. During this phase, I produced numerous sketches, imagining the vases as artifacts that had resurfaced on the coasts of Ayvalık and Mytilene, carried by the current. I envisioned them as having been used in the past to collect and preserve the sounds of the wind. These vases, kept in homes, would have the power to let people hear the echo of places and people once more. Just as you can hear the sound of the sea by holding a seashell to your ear, you can perceive the whispers of a past era.

The collaboration with Santimetre was extremely valuable. In just a few days, I was able to learn the basic techniques of clay work and fully understand its potential. My intention is to create a series of sculptures in the coming months that will become an integral part of the work.

“When I start a new research project, my first step is always to create a music playlist. For me, music is a fundamental tool for immersing myself in the atmosphere and emotions I want to communicate through my work.”

You are not only an artist, but also a cultural worker at PhMuseum in Bologna, Italy. Creative part is vast and limitless, yet operational requirements always fall right opposite of that. Does having operational knowledge also affect your artistic practice?

Absolutely. The two paths constantly intertwine and feed into each other. Working in this field in such a dynamic role (currently primarily as Community Manager and Education Coordinator, while also handling exhibition production and other responsibilities) has allowed me to gain a deep understanding of everything that goes on behind the scenes. This experience has made me much more aware of how to structure my own research and exhibition proposals, among others. It also helps me approach opportunities where I’m invited to exhibit with greater humility. At the same time, being a photographer and visual artist myself, I better understand the needs of other creatives and know how to make them feel welcomed and like an integral part of a community that thrives both online and offline.

It was also exciting to return to Łódź last June for the festival and, this time, experience Photo Match sessions from the perspective of an invited expert. I had the opportunity to review the portfolios of other artists and have constructive discussions about their work. Since I am often on the other side of this process, it was crucial for me to first understand exactly what they were looking for, so I could offer the most useful feedback possible at that stage of their visual research.

What are your inspirations?

When I start a new research project, my first step is always to create a music playlist. For me, music is a fundamental tool for immersing myself in the atmosphere and emotions I want to communicate through my work. Depending on the track, I focus on different elements. Sometimes I prioritize the melodies, looking for sounds that evoke specific sensations, colors, or images. Other times, the lyrics guide me, with their words and stories opening up new perspectives and ideas. I often listen to the same track on a continuous loop for hours, which helps me reach a state of deep reflection and focus entirely on my research, eliminating all distractions and allowing me to delve deeper into the concept I am exploring.

For the project I developed during the residency, the main inspiration came from an extensive collection of love and protest poems by Nâzım Hikmet. Before leaving, I thought that poetry might be helpful, but I was afraid that Hikmet would be a predictable choice. I bought the book on a whim, and when I started reading the first few pages at the beginning of the residency, I was glad I had. Not only did I find numerous references to the sea and the stars, but I was also transported into the sensory and poetic vision I had envisioned for the project. I spent the first week fully immersed in the book, sitting on the pier watching and listening to the boats in the morning and seeing the sunset in the late afternoon. It’s thanks to his verses that I found the key to understanding the project and its title.

It was also beneficial to understand how deeply connected traditional Turkish and Greek music and dances are, with melodies and steps that are often very similar. Although dance is not a visual element in the photos, it is present in the feelings I experienced and in the continuous cultural exchange I observed. Clear examples of this are dances like the Kasap Havası (known as Hasapiko in its Greek version) and the Zeibekiko (or Zeybek in Turkey). Both have intertwined origins in Greek and Turkish culture, resulting from a shared history—an example of how the two cultures have coexisted and influenced each other for centuries.

Thank you, Rosa. It was a fantastic conversation with you. I can’t wait to see each other again. Very soon!