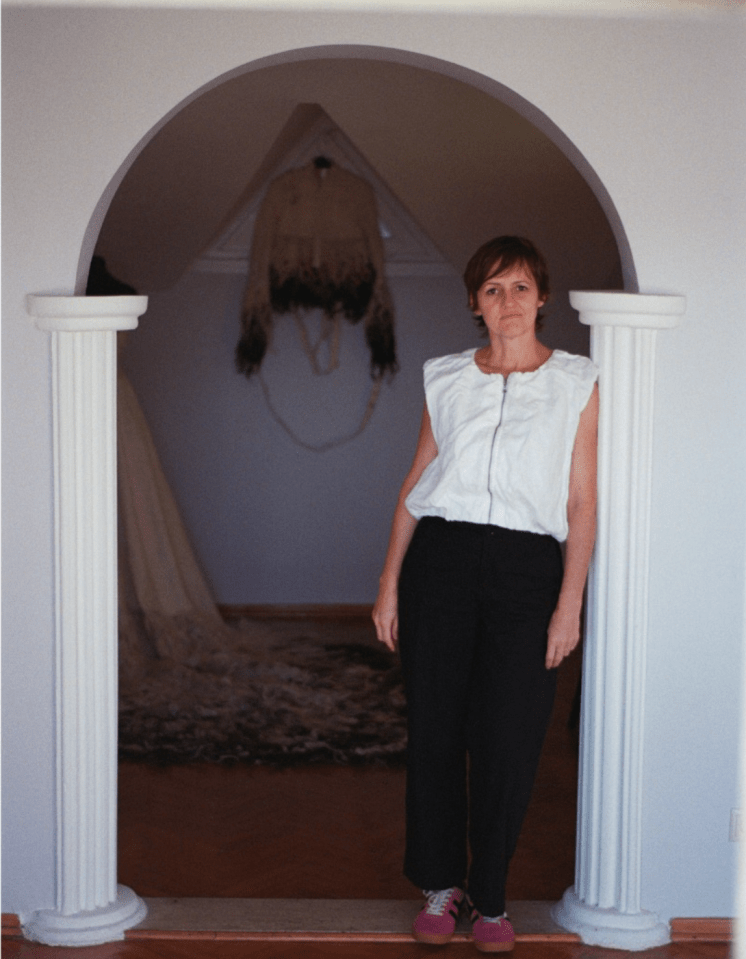

Rast Gallery’s latest exhibition, INNOCIDE, intertwines Nathalie Rey’s and Mesut İkinci’s artistic practices. The exhibition, curated by Begüm Güney and open until November 22nd, invites the audience to reflect on microviolence, memory, and the fragility of the human body through painting, installations, and media works. To me, the most significant aspect of the exhibition is seeing how a performance artist engages with painting and how a painter becomes involved in installation. I wanted to explore the flux between artists’ practices, as reflected in the exhibition’s title, through this interview.

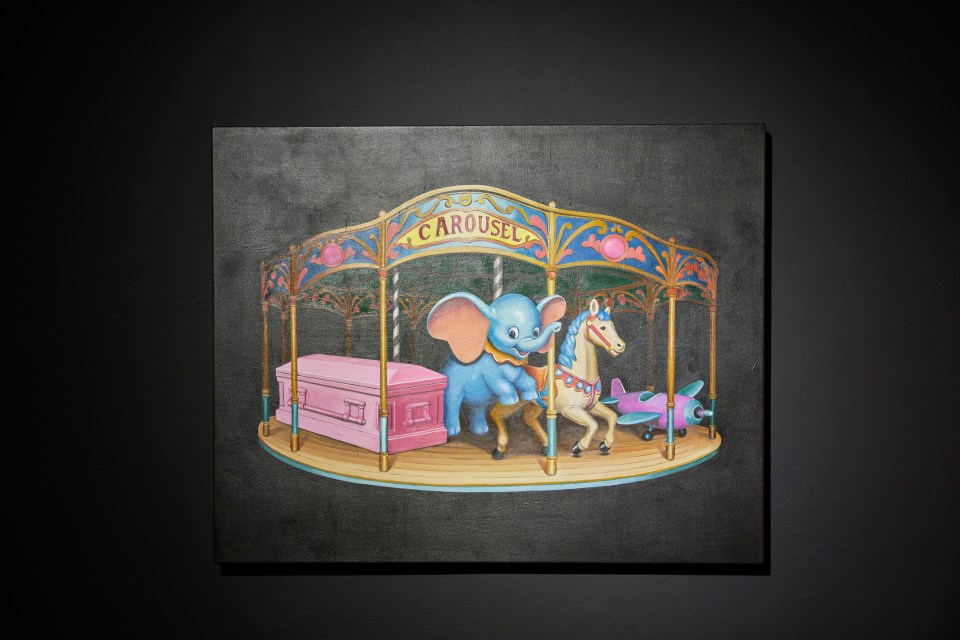

I’d like to start by asking you both some common questions. I would like to begin with the title of the exhibition, which beautifully reflects and brings together your individual practice. Nathalie’s pop images and color choices melt into Mesut’s images, pointing to violence. The works have visual stillness combined with intensity. How did you decide the exhibition’s title?

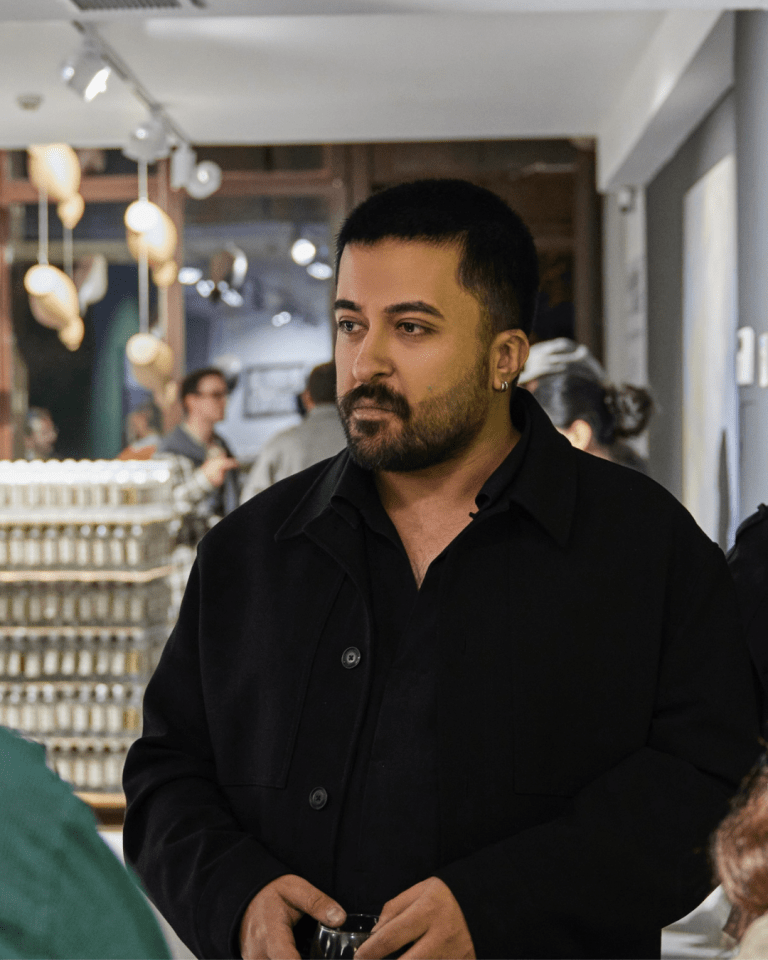

Mesut İkinci (Mİ): Honestly, we decided on the exhibition title after we had already shaped the conceptual framework of the works. Once our discussions around the pieces came to a certain point, we started to think about possible titles. Begüm Güney was quite flexible in that process. Normally, curators tend to define that space themselves and decide on the title, but this time Begüm suggested that it should be a shared decision.

Nathalie Rey (NR): It was actually Mesut who came up with the title. At first, he had proposed another title, War and Plush — inspired by Tolstoy’s novel — which also made sense in relation to the narrative we were trying to build for the exhibition. But in the end, we went for something more abstract, leaning more toward Mesut’s conception of art than mine: a cerebral and conceptual approach, as opposed to my own, which is more narrative, emotional, and rooted in autobiography.

Mİ: We prepared a list together and made the choice collectively. I can say it was truly a mutual decision, very much in line with the collaborative spirit that shaped the entire exhibition process.

We eventually chose “Innocide”, a word that stands at the intersection of “innocent” and “genocide.” It reflects a sense of silent, invisible, everyday violence and destruction that hides within innocence. That feeling connects all of our works in the show: the forms of violence that don’t necessarily explode but quietly circulate through daily life. For us, Innocide became more than just a title; it became the emotional tone of the entire exhibition.

We see various media in the exhibition. Nathalie, until I saw your paintings, I did not know you used to paint. And Mesut, as a painter, was it your first time producing a knitting installation of a rocket? What would you say about your experience of distancing yourself from your regular artistic practice?

Mİ: The installations in this exhibition were new experiments for me. Conceptually, I tried to challenge myself in many ways. I didn’t want it to look like a sharp shift between mediums, from painting to installation. Instead, I wanted it to feel like a softer, more organic transition. I later learned there’s even a term for that: a “soft transition”, not a sudden rupture, but a gradual evolution that grows from within.

To make that transition feel natural, I realized I needed to create intermediary works, pieces that would connect the two languages and reveal their shared conceptual ground. At first, I was a bit anxious, thinking I might struggle with it. But as the process unfolded, I understood that all the media I had been using, whether painting, object, or video, already contained the potential for that transformation.

I experienced this most clearly in my works “Crochet Rocket Experiment” and “Water Experiment.” The rocket represents power and destruction, while water stands for fluidity, memory, and invisible micro-violence. I wanted the water bottles in the exhibition to appear as innocent, everyday objects, yet to carry a subtle sense of threat within that innocence. I was looking for a balance between the rocket’s physical force and the quiet persistence of water: one embodies visible destruction, the other silent infiltration. The tension between those two poles became, for me, a metaphor for that soft transition itself.

NR: In my case, I’d say it was mostly about play. For Mesut, I think it was more of a challenge — even a questioning of his current practice. When we first started talking with Özgür about the idea of a duo show and a collaboration with Rast Gallery, the question came up whether I’d be open to painting again — a practice I had set aside more than ten years ago, with very few exceptions. That request came naturally because Mesut had seen some of my older paintings.

From the very beginning, even before we thought of working together, a very specific dynamic emerged between us — something between play and competition. I think it comes from the fact that we both carry a few insecurities: Mesut, being much younger, and I, being in unfamiliar territory here in Turkey.

But this dynamic made our collaboration quite exciting. It led to a kind of mutual provocation: what if we swapped roles, just to unsettle the audience? It was, once again, a matter of play, challenge, and a bit of mischief.

For me, it was an absolutely strange experience. In a way, I don’t really recognize those old paintings as mine anymore — it’s like looking at someone else’s work. But at the same time, I feel that past and present somehow meet: the awkward past of experimentation and trial and error, and the present of a more mature practice, where I’ve identified the methods and themes that truly matter to me.

How was your experience working together? I assume that even a solo show is challenging. Still, you nailed a duo show, which I find even harder than a group show in terms of creating harmony between different practices and offering alternative perspectives to the audience. From time to time, I could not distinguish which work belonged to whom, and I loved this feeling. Do you see a relationship between each other’s works?

Mİ: To be honest, working together should have been easier for Nathalie, but I might have made it a bit more complicated. I’m used to creating alone, and that solitary process sometimes makes group or duo exhibitions challenging for me. But I should say, and I mean this sincerely, Nathalie made everything much easier. We were in constant communication throughout the process, and I think that played a key role in establishing such a strong harmony between us.

The ambiguity about who created which work was actually something we planned from the very beginning. For Nathalie, these paintings were her firsts shown in Turkey; for me, the installations were my first experiments in that medium. So we thought, “If that’s the case, let’s make it so people can’t easily tell who made what.” We even decided not to include artist names on the labels at first. But a few hours after the opening, when that choice started to create a small sense of chaos, we ended up adding our names. It was an enjoyable, even amusing, experience.

I think the contrast between the works created a very clear connection. That tension and balance between difference and dialogue was essential. When we developed this project with Begüm, we were all in agreement about that approach, and that shared understanding is what made the collaboration truly work.

NR: If you felt that, it means we played our game well! Although, to be honest, I think the game ultimately escaped us.

I often collaborate with other artists or collectives, so I can compare. And I can say that this one wasn’t exactly easy. It’s almost a miracle that the combination of works functions so well — credit to the curator for that. But I suppose we both relied on a kind of intelligence that exceeded our individual intentions, and that’s what made it work. In this duo dynamic, I somehow stepped back a little. Yet, without all these particular circumstances, I would probably never have started painting again.

As for whether there’s a real proximity between our works — I don’t think so. I think it’s circumstantial, related to the fact that we met precisely at a transitional moment in Mesut’s practice. Once he fully embraces the new direction he’s heading toward, I believe our differences will become more visible.

“So even if I had to move on from painting to open my practice to other mediums,

I don’t disown that early stage — I now see it as the seed of what was to come.”

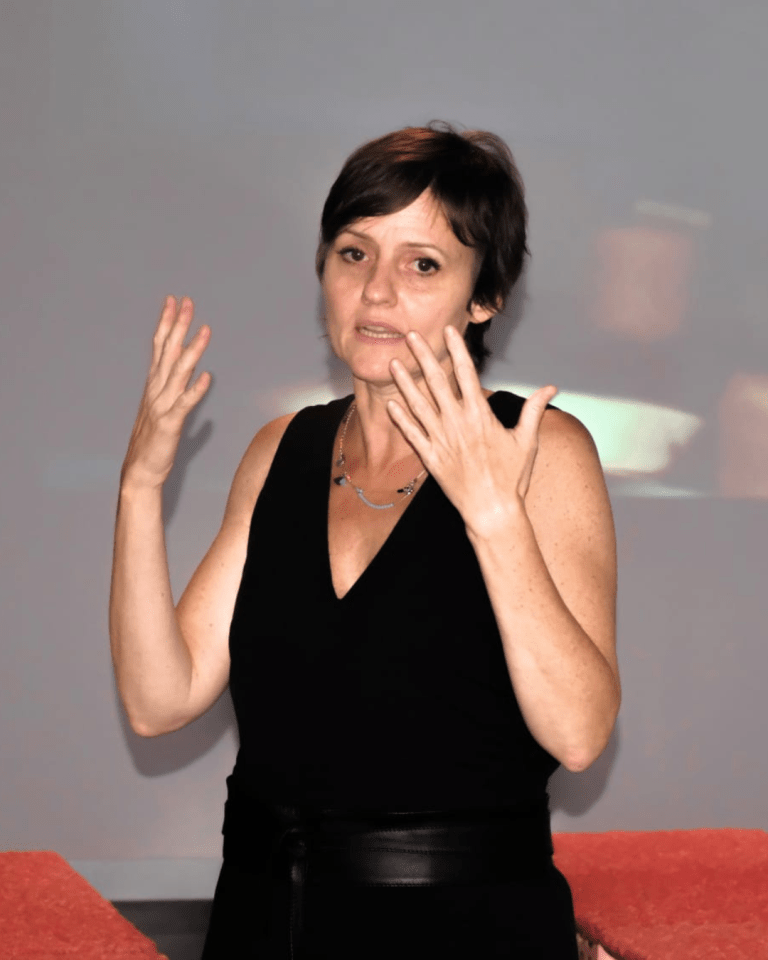

Nathalie, you have been active in Istanbul, and after your residency at Gate 27, your presence has grown significantly. How did you decide to invest in your career in Istanbul? If you compare Istanbul to Barcelona, where you are based, what are the differences and similarities between the two cities in terms of the arts sector?

NR: In a way, my ongoing returns to Istanbul have been less a decision than a chain of coincidences — each visit brings a new collaboration proposal, which then leads to the next visit. And this cycle keeps accelerating!

Of course, if I didn’t enjoy working in Istanbul, I wouldn’t keep saying yes. But there’s something completely euphoric about it — as if anything were possible, any kind of madness! Which might sound paradoxical, but that tension somehow makes it even more stimulating.

Each time I come back, I feel more and more welcomed by the art community. It’s as if I’ve achieved in less than two years in Turkey the level of recognition that took me more than a decade in Catalonia.

I’m aware that it’s not the same to start a career somewhere, like in Barcelona, as it is to arrive in Istanbul with a CV. However, there must be other factors as well — scale, for example. Barcelona has about 1.6 million inhabitants, Istanbul nearly twenty million. So naturally, the art scene is larger here, but also more concentrated and, in some ways, more elitist.

In Spain, the art ecosystem is supported by many public grants — not only for artists but also for galleries and institutions — which keeps the sector afloat but also somewhat saturated. Istanbul’s scene, in contrast, feels younger, more dynamic, and the audience more curious. Maybe my performative and installation-based practice also seems a bit unusual or exotic here, which sparks extra curiosity.

Would resuming your earlier practice, painting, through this exhibition affect your future performances or installations?

NR: It’s too early to tell. I haven’t yet had the time to reflect on that shift. Intuitively, I’d say no — they’ll probably remain separate practices, at least for a while.

Also, please tell us more about the paintings in the exhibition. What were the motivations to include these specific ones?

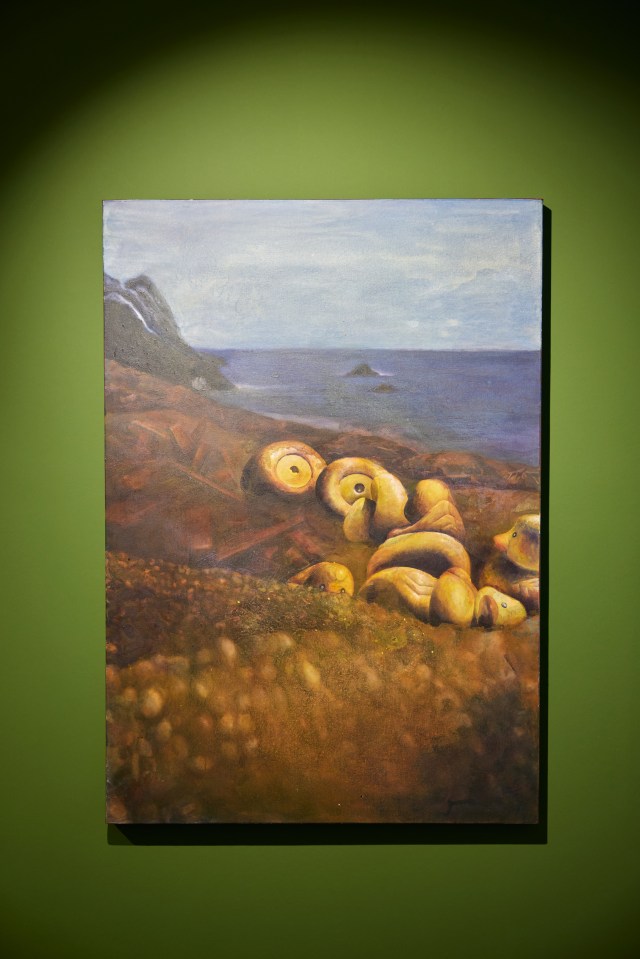

NR: Most of the paintings in the exhibition are old works, made between 2013 and 2014. There wasn’t really a selection process — they’re simply most of what I still have from that period.

At that time, I was mainly working around the idea of “heaps” or accumulation. It was a stage of searching and experimenting, after a previous sculptural phase (my university major), which included the wooden penguins I carved myself.

That series of “heaps” already contained many of the themes that still interest me today: the coexistence of violence and innocence within a single image, the broader framework of consumerism, and what Jean-François Chevrier calls “biographical forms.”

So even if I had to move on from painting to open my practice to other mediums, I don’t disown that early stage — I now see it as the seed of what was to come.

“Like Kapoor’s works, my black areas from that period were born from a desire to confront the invisible. […] That impossibility of seeing, that depth of absence, is precisely where my own work tries to linger.”

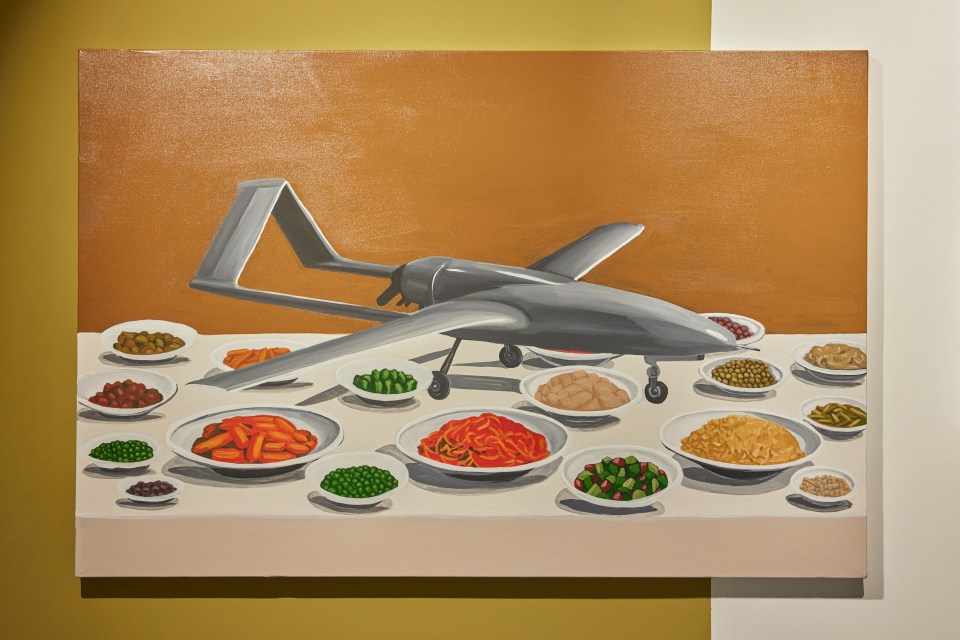

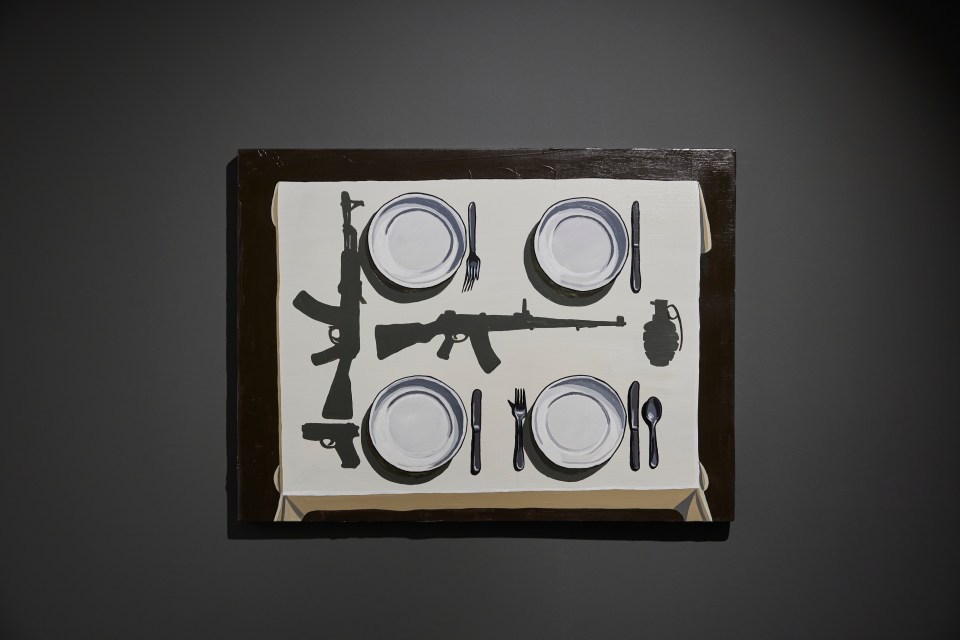

Mesut, I vividly remember seeing your work during the Mardin Biennial last year. The series on display mainly depicted men in suits, surrounded by animals or faces alluding to tortoise shells in public spaces. But in this exhibition, we witness more intimate environments, such as the entrance to a house and a dinner table. Yet, these paintings also include obvious images of machine guns and fighter jets. The works in this exhibition are visually declarative in terms of conveying their message. Is there an intentional shift?

Mİ: Yes, at that time, I was working on a series built around the feeling of grief that follows loss. Looking back now, I call that period my “Black Series.” I believe that traumatic experiences open cracks within us, they tear away fragments of who we are, and those missing parts, to me, can only be represented as black voids. These voids are a kind of memory gap: invisible yet deeply felt, existing somewhere between consciousness and repression.

During that period, I often wandered through urban spaces with animals, searching for those “lost fragments.”

Animals have always reminded me of where everything begins, as if they are travelers of a forgotten human memory. I still want traces of them to appear in my works, though I feel that’s becoming more difficult now. At some point, inside the home, the only wanderer left is the human being.

At that time, a question kept echoing in my mind: “Whose grief is this?”

And I think that period taught me to look inward, not toward the outside world, but toward the interior, the private, the repressed. This inward turn helped me recognize the micro-level forms of oppression and invisible violence that shape everyday life. If I’m shifting my gaze from the macro to the micro, then the images themselves need to become more direct, more precise, to confront the viewer through my own window with a certain clarity. Since then, I feel my imagery has become more intentional and sharply defined.

I’d like to expand a bit on this idea of the “black void.” Even if it’s not directly about animals or humans, I want to explore that metaphor further in my future work. This notion reminds me of Anish Kapoor’s black pigment surfaces that completely absorb light. Like Kapoor’s works, my black areas from that period were born from a desire to confront the invisible. In his piece “Descent into Limbo,” the viewer literally looks into a black void, but cannot see what lies within. That impossibility of seeing, that depth of absence, is precisely where my own work tries to linger.

I have a special interest in the installation, Story of Water. It is written “From Allan Kaprow to Ahmet Öğüt” on the bottle labels forming the installation. Would you tell us about this work? How does this work tie these two artists? And why are they important to you?

Mİ: For me, Story of Water is essentially a timeline, a current that connects two different periods, two different ways of thinking, across the surface of water. The phrase “From Allan Kaprow to Ahmet Öğüt” printed on the bottles was meant to serve as a bridge, not only between two artists, but between two distinct artistic approaches.

Kaprow was the artist who, in the 1960s, carried art into everyday life and broke the sanctity of the art object. His “happenings,” where the lived moment itself became art, remain a deeply radical and inspiring idea to me. In fact, versions of those works continued to be reinterpreted around the world well into the 2000s.

Ahmet Öğüt, on the other hand, reexamines that legacy within today’s political and social contexts. Sharing the same geography with him makes that connection even more meaningful for me. I think Öğüt’s works search for ways to question the system from within, and he does it through profoundly striking works.

My installation, Story of Water, stands exactly between these two lines of thought. Here, water becomes a metaphor for both life and violence, innocent, transparent, and indispensable on one hand; yet on the other, capable of seeping into everything, dissolving everything it touches. The industrial order of the bottles and the standardized language of their labels point to the invisible micro-violence embedded within systems of production and consumption. That’s why I designed the labels with a military camouflage aesthetic, to construct a visible critique through the language of invisibility.

By bringing together Kaprow’s idea that “life itself is art” with Öğüt’s notion of “resisting from within the system,” I wanted to treat water as both a site of action and a form of witnessing.

And along this timeline, there is one thought that feels central to me

The value of art is not measured by its distance from the system, but by how deeply it can touch it.

I hope that, in the future, this timeline continues, that a fourth link will be added by another artist from Turkey, allowing the flow to find its own path forward.

You recently moved to New York City, where you live and work. What are the new experiences for you in NYC? How did this move impact your practice?

Mİ: It’s been almost a year since I moved to New York, though I’ve been in Istanbul for the past four months preparing for this exhibition. I’ll be returning to New York in November — there are a few projects waiting for me there.

During my first months in New York, I spent most of my time visiting exhibitions, studios, and artistic spaces. I felt I needed to understand what was happening in the art world, and I’ve never been afraid of being influenced by other artists. When I encounter strong works, I don’t like to stand on the sidelines; I prefer to step right into them.

New York is an incredible source in that sense. What I experienced there pushed me away from figuration and body-centered narratives, and toward the more conceptual works that are now part of this exhibition. It may sound radical, but I honestly think mediums have lost their authority there. In New York, as one of the major centers of global art, art no longer functions as a medium or a tool; everything revolves around purpose and concept. That realization was transformative for me.

So I can say that New York didn’t just change my artistic practice, it also made me a more social, open, and connected person.